Turning out in his home province at a major tournament for Argentina, Lionel Messi was introduced as “the best in the world” by the stadium announcer at Santa Fe’s Estadio Brigadier General Estanislao Lopez.

The response was polite applause. Fair enough: perhaps the locals were nervous following a lacklustre opening draw against Bolivia in the 2011 Copa America. There was little room for further error with Colombia in town.

Next up, after Messi’s No. 10, was the Albiceleste’s No. 11. “The player of the people, Carlos Tevez!” The masses roared. The Manchester City forward, who would soon embark upon an extended mid-season golfing holiday after a bust-up with club boss Roberto Mancini, was the object of their affections. Not Messi, the man who had just won his second Champions League in three seasons at Barcelona and was two Ballons d’Or into an unbroken four-year run.

MORE: Ballon d’Or winners: Who won the most? Lionel Messi, Cristiano Ronaldo, and others

This outpouring of affection for Tevez on Messi’s turf offered a snapshot of the discussions and presumptions over Argentina’s star player as he entered his prime years. His otherworldly quality was beyond question but Messi increasingly came up short in the popular imagination in terms of intangible and shifting measures of authenticity.

¡Una de las ediciones más sorprendentes de la CONMEBOL #CopaAmérica fue en el año 2011, una edición repleta de figuras, goles y momentos destacados. ¡Revívela! 🏆#VibraElContinente pic.twitter.com/vmvjDYSVLN

— Copa América (@CopaAmerica) February 3, 2021

A century ago, Argentina was the birthplace of what might be referred to today — derisively or otherwise — as football hipsters. Writers working for the influential sports magazine El Grafico wrote in romantic terms about how the sport brought to South America as a well-mannered British game had developed a uniquely Argentinian edge as it evolved within burgeoning working-class communities. This amounted to greater cunning, improvisation and trickery, underpinned by a sleight-of-hand if required.

The writer Ricardo Lorenzo, better known by his pseudonym of Borocoto, felt this democratisation of football made it as fundamental to the Argentine experience and identity as tango music. As recounted by Jonathan Wilson in his book on the history of football in Argentina, Angels With Dirty Faces, in 1928 Borocoto described raising a statue to the imagined inventor of dribbling.

“A pibe (a kid/urchin) with a dirty face, a mane of hair rebelling against the comb; with intelligent, roving, trickster and persuasive eyes and a sparkling gaze that seems to hint at a picaresque laugh that does not quite manage to form on his mouth, full of small teeth that might be worn down through eating yesterday’s bread,” Borocoto began.

“His trousers are a few roughly sewn patches; his vest with Argentinian stripes, with a very low neck and with many holes eaten out by the invisible mice of use. His stance must be characteristic; it must seem as if he is dribbling with a rag ball. This is important: the ball cannot be any other. A rag ball and preferably bound by an old sock.”

For all his inimitable gifts, as a middle-class kid from Rosario, Messi had not had to spend too much time chewing on yesterday’s bread and kicking around a rag ball in careworn clothing, even before Barcelona and their European riches uprooted Leo and his family, bringing them to Catalonia when he was 13 years old. Tevez, on the other hand, fitted this archetype like a glove, with his rampant playing style, unruly appearance and tough upbringing on the dangerous streets of Fuerte Apache all part of the same whole.

MORE: MESSI & RONALDO: DESTINATION MUNDIAL | HOME

As Wilson points out, Borocoto did an eerily excellent job of describing Diego Maradona more than half a decade before his 1980s heyday. El pibe de oro — the golden boy — was one of Maradona’s most enduring nicknames in Argentina. His upbringing was pure Tevez and he scrapped his way to riches on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, as opposed to being hand-picked for stardom.

These differences with Messi should have been nothing more than trivial banalities but as the Barcelona hero made a strong case for being the best player in the world, Argentina fans began to wonder why they were not seeing the full benefits of that.

Such unflattering comparisons were thrown into sharp focus in late 2008 when, despite minimal and largely unimpressive prior coaching experience, Maradona was sensationally appointed as Argentina boss.

Veteran coach Alfio Basile, who led La Albiceleste to back-to-back Copa America triumphs in 1991 and 1993, returned to the national team when Pekerman resigned in the aftermath of the 2006 World Cup. He was within a game of a third Copa before losing the 2007 final to Brazil. A year later, after a poor start to qualification for the 2010 World Cup, Basile resigned.

Sergio Batista, who led Messi and Argentina’s Under-23s to gold at the Beijing Olympics, was viewed as the frontrunner, but Maradona publicly declared his interest and momentum irresistibly built behind a national hero like no other.

The Argentinian Football Association, under long-serving president Julio Grondona, was typically swayed by cynicism over stability and Maradona was duly appointed. The logic, insofar as any existed, was that this magnificent generation of players did not need a meddling coach to thrive; they simply needed inspiration. And who better to do that than God himself?

Maradona certainly approached his work with a missionary zeal, spreading his message far and wide by implausibly calling up more than 100 players during his two years in charge. These numbers are skewed slightly by some friendlies where the squad comprised solely domestic-based players, but it’s still a staggering figure.

Amid a pervading sense of perma-chaos, a place at the 2010 World Cup was secured, despite Messi scoring a solitary goal in the eight qualifiers he played under Maradona.

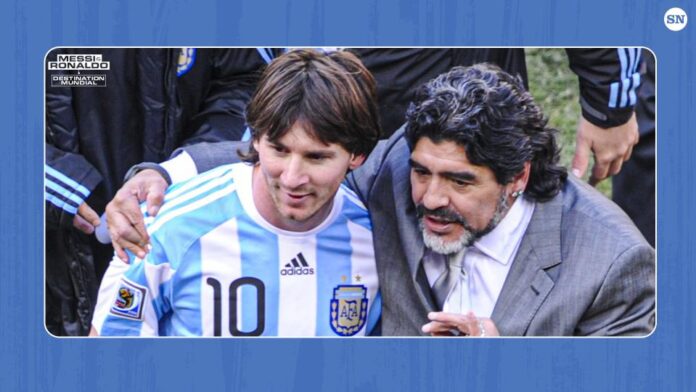

The perpetual, suffocating comparisons did not prevent Messi and Maradona from sharing a warm personal relationship, with their mutual affection often visible. Messi credited his coach for helping him to improve his free-kick technique, another area where he became among the very best on the planet. Before heading to South Africa, the two met in Barcelona and decided Messi would play as the No. 10 behind two strikers in a 4-3-1-2 formation.

It was a role Leo relished, but one only opened up after Maradona cast aside Juan Roman Riquelme — the playmaker who had been such an ally to Messi at international level.

Feliz cumpleaños Carlos Tevez! 🎂🇦🇷

What better way to celebrate than reliving this superb strike from the 2010 #WorldCup?💥@Argentina | @BocaJrsOficial pic.twitter.com/Npbm0gsnnR

— FIFA World Cup (@FIFAWorldCup) February 5, 2020

Maradona’s freewheeling, attacking Argentina surged through the group stage with three wins out of three. Messi didn’t score but he was as integral as hoped to their overall play. Still, some of the quirkier selections after 100-plus players were filed down to a 23-man squad continued to jar.

Newcastle United winger Jonas Gutierrez was a favourite of Maradona’s, so much so that he found a place for him in the team at right-back. That made only slightly more sense in the context of failing to pick either Inter’s Champions League-winning captain Javier Zanetti or Pablo Zabaleta for the tournament, but selecting and then never fielding 30-year-old Colon defender and four-cap novice Ariel Garce.

After a riotous 3-1 win over Mexico in the last 16, Maradona replaced Gutierrez at right-back with Nicolas Otamendi and Germany thundered to a 4-0 win to end his dream.

“Anyone saying [Messi] didn’t have a great World Cup is an idiot,” Maradona said afterwards. The only problem was, on that basis, there were a growing number of idiots back home. Maradona and all his coaching eccentricities were beyond reproach. When he was the best player in the world, he led Argentina to glory in 1986. Why couldn’t Messi, in his feathered Catalan existence, do the same?

Such attitudes hardened when Argentina hosted the 2011 Copa America. Batista now had the top gig and configured a side around Messi playing as a false nine. They proved to be a dour version of Barcelona. The game in Santa Fe, where Tevez was roared and Messi ignored, finished 0-0. A 1-1 draw in the quarter-final with Uruguay was their third stalemate in four matches and ended in a penalty-shootout defeat.

Three of Argentina’s five goals in the finals came against Costa Rica and Messi, for the second consecutive major tournament, did not score at all. For some, the second coming had started to feel like a pale imitation.

Credits and acknowledgements

The Sporting News was fortunate enough to speak to a number of experts on Portuguese and Argentine football to enhance the Messi & Ronaldo: Destination Mundial series. We would like to thank the following people for their time and input – please do check out their superb work.

Santi Bauza: Argentinian football journalist and content creator, whose credits include Copa 90, CNN and Hand of Pod.

Dan Edwards: Freelance football journalist based in Argentina, formerly the long-time South America correspondent for Goal.com.

Peter Coates: Editor of Golazo Argentino.

Simon Curtis: Portuguese football expert and co-author of The Thirteenth Chapter.

Aaron Barton: Creator of English-language Portuguese football destination Proxima Journada.

Tom Kundert: Creator of PortuGOAL and co-author of The Thirteenth Chapter

Joshua Robinson & Jonathan Clegg: Wall Street Journal sports reporters and authors of Messi vs. Ronaldo: One Rivalry, Two GOATs, and the Era That Remade the World’s Game

READ: PART 5 | CRISTIANO AND EUSEBIO (Published Thursday, November 17 12:00 GMT / 07:00 ET)

Hits: 0